“Stephen’s living face was as the face of an angel. Brother Kline’s dead face was the face of a saint—no, not the face of a saint, but the face of the earthly casket in which a saint had lived, and labored, and rejoiced; and out of which he stepped into the glories of the eternal world. Amen!” (Benjamin Funk, Life and Labors of Elder John Kline: The Martyr Missionary, 1900)

Born on June 17, 1797, in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, John Kline became the most significant martyr in the history of the Brethren denomination, but his death is but a footnote in the long and storied saga of the men and women who struggled to be true to the teachings of Jesus and the primitive church. Their history actually begins in the mother country, specifically the German city of Schwarzenau (currently located in Austria).

“The Schwarzenau Brethren organized in 1708 under the leadership of Alexander Mack (1679-1735) of Schwarzenau, Germany. They believed that both the Lutheran and Reformed churches were taking liberties with the “true” Christianity revealed in the New Testament, so they rejected established liturgy, including infant baptism and existing Eucharistic practices. The founding Brethren were broadly influenced by Radical Pietist understandings of an invisible, (nondenominational) church of awakened Christians who would fellowship together in purity and love, awaiting Christ’s return.” (Religion Wiki)

Persecution drove these early Brethren, or New Baptists as they were known at that time (the name was used to distinguish them from the “old” Anabaptist groups), from their homeland, and many of them migrated to the Pennsylvania colony in 1719 under the leadership of Peter Becker. They initially found a safe haven with the Quakers, but their “trine baptism” (being immersed three times to symbolize the three persons of the Trinity) soon earned them the pejorative label “Dunkards.” Again, experiencing the ostracism of their community, these early Brethren migrated south and west, many relocating in what was called “The Great Valley of Virginia,” or the Shenandoah Valley as it is known today. It’s this group that formed the seedbed for the current Church of the Brethren denomination … or as they were known during Elder Kline’s life – the German Baptist Brethren.

“Continued settlement from Pennsylvania and Western Maryland established a route through the Shenandoah Valley that later became known as the “Great Wagon Road.” Countless German and Scots-Irish settlers travelled this route during the mid-1700s in order to cross into the Virginia frontier (the Great Wagon Road later transformed into the ‘Valley Turnpike’ during the mid-1800s, and it is known today as ‘Route 11’).” (www.localhistory.rockingham.k12.va.us/john-kline1.html)

John Kline’s family also left the familiar confines of Dauphin County and settled on the western bank of “Linvell’s Creek” which was named for William Linvell (aka William Linvel or William Linwell), a land speculator who was granted 1,500 acres of prime farmland in that area. John was fourteen at the time. At age 21, John married Ana Wampler and soon built a house on the east side of “Linvell’s Creek” in what is now known as the town of Broadway. The house was meant to serve as a homestead and as a Brethren meeting house. The living quarters contained three walls that were hung on hinges so that they could be moved out of the way for services and council meetings. In 1825, John gifted a large portion of his land to the Brethren congregation at Linville Creek for a more permanent meeting house, a gift that actually served two ministry purposes: not only provide a place for a permanent meeting house, but also to furnish sufficient space for a cemetery. This gift was later developed to house the current Linville Creek Church of the Brethren.

Kline’s service to the church went far beyond land donations, though; in 1827 he was called to serve the church as a deacon, three years later as a minister of the first degree, and then five years after that as an elder. Even though his congregation continued to grow, Kline served without remuneration in keeping with the Brethren “free ministry system;” in order to “make ends meet,” though, he needed to continue to work his farm while taking care of his elder responsibilities. Not only did Kline serve the congregation at Linville Creek, but he travelled extensively throughout southwest Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, Ohio, and Indiana preaching the Gospel, encouraging the Brethren congregations, and planting churches. In fact, The Brethren Encyclopedia estimates that between 1843 and 1863, Kline probably travelled over 100,000 miles as a Brethren missionary.

The advent of the “War between the States” presented the Brethren community with a number of dilemmas. On January 1, 1861, Kline wrote this in his diary:

“The year opens with dark and lowering clouds in our national horizon. I feel a deep interest in the peace and prosperity of our country; but in my view both are sorely threatened now. Secession is the cry further south; and I greatly fear its poisonous breath is being wafted northward towards Virginia on the wings of fanatical discontent … Secession means war; and war means tears and ashes and blood. It means bonds and imprisonments, and perhaps even death to many in our beloved Brotherhood, who, I have the confidence to believe, will die, rather than disobey God by taking up arms.”

The staunch anti-slavery view of the Brethren brotherhood seemed to clash vehemently with its concurrent anti-secession view. Add to this the Brethren’s passionate conviction opposed to taking up arms, and you can only imagine the quandary the Civil War presented the community. Two incidents seem to sum up the issue’s relevance to the struggle men like Kline experienced.

The first was the actual vote that the state of Virginia took on the referendum to secede from the Union. Elder Kline voted at the polling station located in Mt. Crawford on May 23, 1861. Due to constant secessionist pressure, the community leaders expected the vote to be unanimous in favor of seceding. When the votes were counted, however, the tally was 258-1 to authorize the state of Virginia to secede.

“(O)n the day of the vote and supposedly sometime before noon, the Elder John Kline rode in and cast his ballot. As he rode away, the questions began to arise in regard to Kline’s standing against slavery and secession. When the suspense proved too much, the ballot box was opened and the one opposed vote found inside. Determined to keep his jurisdiction solidly secesh, the angry Roller (Judge Peter Roller), his sons and a few other men quickly mounted in an effort to catch the Dunker minister and persuade him to vote otherwise. Having … overtaken Kline at the Carpenter farm, the posse drew their pistols and ordered Kline to return and change his ballot. The minister, feeling that his life was more important than a lone vote, returned, changed his ballot, and rode away again without being made a martyr.” (Robert H. Moore, II, Southern Unionists Chronicles, “Confederate Treatment of a Brethren Elder: Elder John Kline’s Story”, 2008)

The second incident was the nature of Kline’s two-week incarceration at the Rockingham County Court House jury room in Harrisonburg, Virginia.

“(T)he Brethren doctrine of non-violence led them to oppose military service as well. When rumors spread of a Confederate conscription law during the Spring of 1862, about ninety Brethren and Mennonite men abandoned their homes in the Shenandoah Valley and fled west in order to escape from serving in the Confederate Army … At the same time, Elder Kline and several Mennonite and Brethren leaders were arrested and imprisoned in the jury room of the Rockingham County Court House because of their public opposition to military service. These prisoners served a two week sentence while Confederate officials questioned them about their religious beliefs.” (www.localhistory.rockingham.k12.va.us/john-kline1.html)

The suspicion surrounding Kline and the Brethren teaching would ultimately be his undoing. Because he took no side in the conflict, he ministered physically and spiritually to Union and Confederate soldiers alike. As you can imagine, his non-partisan behavior engendered mistrust from both the Blue and the Gray!

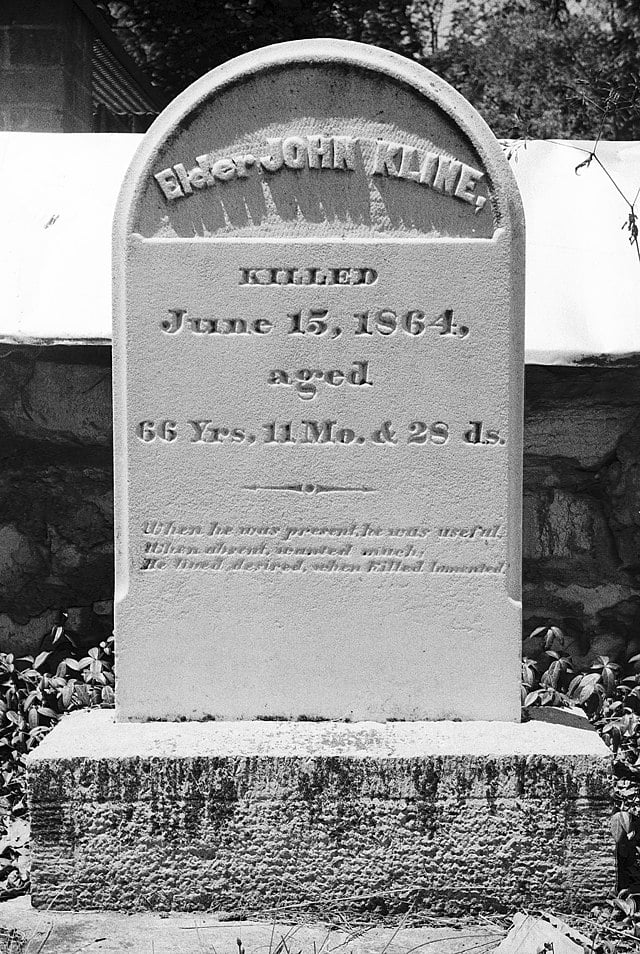

“Elder Kline moderated four annual meetings during the Civil War; he held three of the four meetings (1862, 1863, and 1864) in the North. Not long after returning from the last meeting at Nettle Creek Church in Indiana, and after repairing a clock at a church member’s house four miles west of his home, Elder John Kline was killed on June 15, 1864, by a few local Confederate irregulars unsympathetic to his cause.” (Robert H. Moore, II, Southern Unionists Chronicles, “Confederate Treatment of a Brethren Elder: Elder John Kline’s Story”, 2008)

Elder John Kline is buried in the Linville Creek Church of the Brethren Cemetery located in Broadway, Virginia.

Featured Image Credit: Wikipedia contributors. “John Kline (Elder).” Wikipedia, 8 Aug. 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Kline_(elder).

Related

Sorry, no records were found. Please adjust your search criteria and try again.

Sorry, unable to load the Maps API.