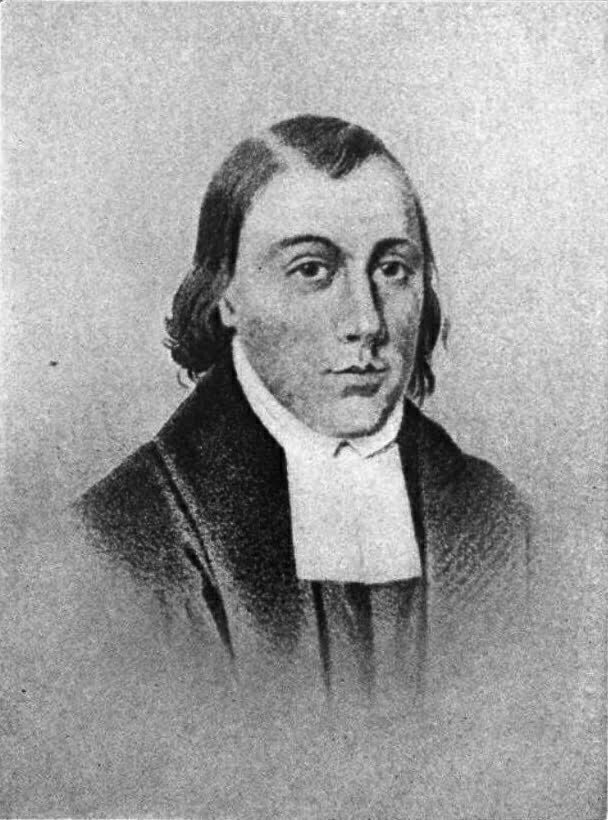

John Blair Smith was the second president of Hampden-Sydney College, founded by his older brother.

From Banner of Truth:

This was certainly true at Hampden-Sydney and the President, John Blair Smith, also a Presbyterian pastor of two nearby, small congregations, Briery and Cub Creek, was deeply grieved. He and the members of his churches began to pray for revival in their communities and at the college. In 1788 eighty young men were at the college and none were outwardly professing Christians. It had become vogue to reject the Calvinistic upbringing these young men had received. But two students, William Hill and William Calhoun, found each other and admitted they were concerned for their souls. When Calhoun read Alarm to the Unconverted1, a Puritan classic by Joseph Alleine, he became even more concerned for his soul. The two agreed to pray secretly on Saturdays in the woods, lest other students see them and mock them. But one Saturday they were expecting rain so they decided to pray in the residence hall. Others heard them praying and threatened to break down the door if they persisted. Later that day John Blair Smith heard about the incident and invited these young men (others had since joined their ranks) to come to his study the next week and pray. Within weeks half the student body was gathering for prayer. There was much weeping, repenting, and rejoicing. Revival had come to the student body at Hampden-Sydney and the communities within one hundred miles of there. Blair’s father, Robert, who had been converted forty years before under the preaching of George Whitefield, after hearing of the revival, came for a look. He had this to say:

From Vance Christie:

Of the nearly eighty students at Hampden-Sydney College in the fall of 1787, only one was definitely known to be a Christian while two others were earnestly seeking after Christian truth. Those three began to meet for prayer on Saturday afternoons, but in the woods some distance from campus so they would not be discovered by their fellow students.

One afternoon rain threatened, so the trio met in one of the college rooms. After locking the door, they began to sing and pray quietly, not wanting to be overheard. But they were found out, and a large group of students quickly gathered in the hallway, banging on the door, yelling, swearing and threatening if the trio did not cease and desist all such spiritual exercises at the college.

Two professors arrived at the scene of the ruckus and ordered all the students back to their rooms. That evening the entire student body was called together, and President Smith demanded to know the cause of the disturbance and who had led it. The leaders confidently stepped forward and stated that they had found a few of their fellow students “carrying on like the Methodists” and they were “determined to break it up.” Rather than condemning the participants in the small prayer group, Smith publicly commended them and invited them to hold their prayer meeting in his parlor the following Saturday.

People were greatly surprised when one week later Smith’s parlor was completely filled by the number of people who attended the prayer meeting. Surprise turned to amazement when just one week after that nearly the entire student body and many neighbors from around the college showed up for the prayer meeting, overflowing the parlor and other rooms of Smith’s home! As more neighbors heard of what was happening at the college, they all wanted to attend subsequent Saturday prayer gatherings. Those needed to be held in the large College Hall, which was filled for the weekly prayer sessions.

From Rev. Dr. James Lewis MacLeod

The year 1787 was an important year at Hampden- Sydney for a reason absolutely no one could have guessed at the time. There began the second Great Awakening, a series of revivalistic tremors to shake American religion and change American religion forever. In the autumn of 1787 a Presbyterian student, Cary Allen, went to a revival meeting in an Anglican Church held by a Reverend Hull, who seems to have been a Methodist. During the meeting he began the holy jerks, groaning, shaking, and trembling, which climaxed by his falling to the floor. Allen said he surrendered to God there on the floor, and arose changed. Shortly after, but not at this meeting, three others were converted, and soon the four were holding secret prayer meetings. This kind of emotional prayer meeting naturally could not remain secret long.

A Faithful Narrative by Jonathan Edwards, a work describing the conversion of many hundreds in Northampton, Massachusetts, in 1735, describes something near this: “Commonly persons’ minds immediately before this discovery of God’s justice are exceedingly restless, and in a kind of struggle and tumult, and sometimes in mere anguish; but generally as soon as they have this conviction.., they then come to a conclusion within themselves that they will lie at God’s feet, and wait his time, and they rest in that, not being sensible.” That there were some defects in this system of grace was freely admitted in Chapter 5, “Defects and decline of the work “ in which Edwards said, “a gentleman of more than common understanding… exceedingly concerned about state of his soul.. .kept awake night, meditating.. .so that he had scarce any sleep at all” finally decided his condition as a sinner was hopeless and cut his throat.

This excessive emotionalism naturally disturbed urbane President Smith; however, he was wise enough not to make martyrs of the young men by turning them out. Indeed he asked them to hold their prayer meeting in his parlor, and naturally everyone wanted to come. Revivalism became the fashion, but Smith tried to keep a Presbyterian discipline of order upon it. For instance, Methodist and Baptist revivals in the area enjoyed leaping, falling down, screaming, groaning, kicking and shouting, but if any of this happened during Smith’s worship services, he paused to say, “God is not the author of confusion, but of peace.. you must compose yourself.” By such means Smith was able to contain revivalism at Hampden-Sydney. In fact, by dignity and order, he used it to some advantage. But it could not be contained elsewhere. The revival spread to another Presbyterian school, Liberty Hall (later Washington and Lee), and then to Kentucky, where the Presbyterians began revivals but soon found them too much to cope with.

Featured Image Credit: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Related

Sorry, no records were found. Please adjust your search criteria and try again.

Sorry, unable to load the Maps API.