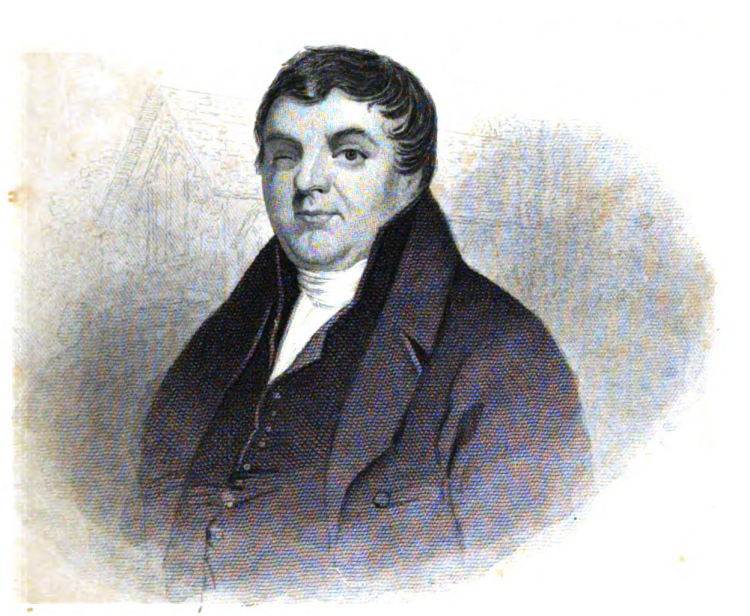

Named for the day of his birth, Christmas Evans (1766-1838) was an unlikely evangelist. When he was saved in 1783 he could not read or write. David Larsen records that “Evans was called the John Bunyan of Wales, the One-Eyed Man from Anglesea, and the prophet sent from God.” Eventually, he taught himself Greek and Hebrew to better preach – and eventually English, although most of his preaching was in Welsh.

Joseph Cross says “Many a David went forth to meet the Philistine, and returned in triumph. One of these, and the most successful of them all, was Christmas Evans. ‘“He was a man of God,” says Dr. Cone, “and eminently useful in his generation.” His natural talents were of the highest order, and his Christian graces have not been surpassed in a century. The celebrated Robert Hall regarded him as the first pulpit genius of the age. “Had he enjoyed the advantages of education,” writes one who knew him well, and often sat under his ministry, ‘‘he might have blended the impassioned declamation of Whitefield with something of the imperial opulence and pomp of fancy that distinguished Jeremy Taylor.”

Christmas Evans, second son of Samuel and Joanna Evans, was born at Ysgarwen, Cardiganshire, South Wales, on the 25th of December, 1776. His birth happening on Christmas day suggested his Christian name.

Samuel and Joanna Evans were poor, and unable to educate their children; and at the age of seventeen, Christmas could not read a word. When he was only nine years old, he lost his father – and went to live with his uncle, who was a farmer, and a very wicked man. Here he spent several years of his youthful life, daily witnessing the worst of examples, and experiencing the unkindest of treatment. He subsequently engaged as a servant to several farmers successively in his native parish.

During these years he met with a number of serious accidents, in some of which he narrowly escaped with his life. Once he was stabbed in a quarrel. Once he was so nearly drowned as to be with difficulty resuscitated. Once he fell from a very high tree, with an open knife in his hand. Once a horse ran away with him, passing at full speed through a low and narrow passage.

PROFESSION OF RELIGION.

His first religious impressions he dates from his father’s funeral. But they were fitful and evanescent. To use his own language, “They vanished and recurred once and again.” When he was eighteen years of age, an awakening occurred among the young people of his neighborhood. Christmas himself was “much terrified with the fear of death and judgment,” became very serious in his deportment, and joined the Arminian Presbyterians at Liwynrhydowen.

His Christian experience was evidently very imperfect. He had a conviction of the evil of sin, and a desire to flee from the wrath to come; but no evidence of acceptance with God, and a very limited knowledge of the plan of salvation. Yet his religious impressions were not entirely fruitless, They produced, at least, a partial reformation of life, and led to many penitential resolutions.

He thought much of eternity, and was frequent in secret prayer. He soon felt a strong desire to understand the Scriptures, and with this view began to learn to read. According to his own account, “There was not one in seven in those parts at that time that knew a letter.” Almost entirely unaided, he prosecuted his purpose; and in an incredibly short time was able to read his Bible.

COMMENCEMENT OF PREACHING.

He was now called upon to exercise his gifts in public prayer and exhortation. ‘To this,” he says, ‘I felt a strong inclination, though I knew myself a mass of spiritual ignorance.” His first performance was so generally approved, that he felt greatly encouraged to proceed. Shortly afterward, he preached a sermon at a prayer-meeting, in the parish of Llangeler, county of Caermarthen.

The discourse, however, was not original, but a translation from Bishop Beveridge. He also committed one of the Rev. Mr. Rowfands’ sermons, and preached it in the neighborhood of the church to which he belonged. A gentleman who heard him expressed great astonishment at such a sermon from an unlettered boy. The mystery was solved the next day; he found the sermon in a book.

“But I have not done thinking,” said he, “that there is something great in the son of Samuel the shoemaker, for his prayer was as good as the sermon.” His opinion of the young preacher would probably have suffered some farther abatement, if he had known, what was the fact, that the prayer itself was memorized!

Young Evans now received frequent invitations to preach, in sundry places, for different denominations; especially in the Baptist church, at Penybont, Llandysil. He spoke occasionally in the pulpits of several eminent ministers. All who heard him were delighted with his discourses, and gave him much encouragement.

These labors drew him into the society of many- excellent Christians. He seems to have profited by their godly conversation, and soon acquired an experimental knowledge of justification ‘by faith, though the witness of the Spirit was not so clear as in many cases, and he could never fix upon any particular time when he

obtained the blessing.

BACKSLIDING AND RECOVERY.

The young preacher shortly felt the need of a little more learning, to qualify him for his calling. He commenced going to school to the Rev. Mr. Davis, his pastor, and devoted himself for about six months to the study of Latin, This involved him in pecuniary distress. He took a journey into England, to labour during the harvest season, for the purpose of replenishing his purse, and enabling him to continue his studies. While thus engaged, he fell into temptation, and his religious feelings suffered a sad declension. He thought of relinquishing the school and the ministry, and devoting his life to secular pursuits. While revolving this matter in his mind, the children of the wicked one came upon him, and buffetted him back to his duty. He was waylaid by a mob, who had determined to kill him. They beat him so severely, that he lay for a long time insensible ; and one of them gave him a blow upon his left eye, which occasioned its total blindness through the rest of his life.

“That night,” says he, ‘I dreamed that the day of judgment was come. I saw Jesus on the clouds, and all the world on fire. I was in great fear, yet crying earnestly, and with some confidence, for his peace. He answered and said: ‘Thou thoughtest to be a preacher; but what wilt thou do now? The world is on fire, and it is too late!’ On this I awoke, and felt heartily thankful that I was in bed.”

This dream produced a deep impression upon his mind, and recovered him from his spiritual declension. He began to preach with renewed energy and success, and all his friends predicted that he would “yet become a great man, and a celebrated preacher.”

CHANGE OF VIEWS.

There was living, about this time, at Aberduar, a Mr. Amos, who had left the Arminian Presbyterians, and joined the Calvinistic Baptists. He came to visit young Evans, and converse with him on the subject of baptism. The latter was unpractised in arguement, and little acquainted with the Scriptures. He strove strenuously for a while, but was at length silenced by the superior skill of his antagonist. Encouraged by his success, Mr. Amos made him another visit, during which he shook his faith in the validity of infant baptism. After this he came again and again.

Mr. Evans was at length brought to believe there was no true baptism but immersion by a Baptist minister. Now it was suggested that he ought to be immersed. Other Baptist friends interested themselves in his case, and put into his hands such books as were best adapted to their purpose. He was shortly satisfied what was his duty. “After much struggling,” says he, “between the flesh and the spirit, between obedience and disobedience, I went to the Baptist church at Aberduar, in the parish of Llanybyther, in the county of Caermar then. I was cordially received there, but not without a degree of dread, on the part of some, that I was still a stout-hearted Arminian.”

He was baptized with several others, by the pastor, Rev. Timothy Thomas, in the river Duar, and admitted to the communion of the church. This was in 1788, when Mr. Evans was about the age of 22.

It is not strange, that, after such a change, he should gradually imbibe the doctrine of election, and its concomitants, as held by the Calvinistic Baptists; but it is quite evident, not only by inference from his own account, but by information from other sources, that he had not yet relinquished his Arminian theology. Whether he would have been more pious and useful, by adhering to his Arminian views, and remaining among his Arminian friends, is a question not for us to answer, and perhaps of little practical importance. It is certain that he became a Calvinist of the highest school, and “a burning and shining light”? among his Baptist brethren. That the Calvinistic faith is not incompatible with eminent holiness of life, we have other evidence than that afforded by the history of Christmas Evans. The seraphic piety of a Bunyan, a Baxter, a Whitefield, and a Payson, should silence for ever the clamors of Arminian bigotry !

DEPRESSING VIEWS OF HIMSELF.

For several years after this, Mr. Evans entertained painfully depressing views of his Christian character and ministerial talents. He thought every other believer had more light than himself, and every other preacher greater gifts. He called himself “a mass of ignorance and sin.” He imagined his discourses entirely useless to his hearers. This he attributed partly to his habit of repeating them memoriter. Others appeared to him to speak extemporaneously, and he “thought they received their sermons directly from heaven,” while he, by memorizing his, forfeited the aid of the Holy Spirit. “I therefore changed my method,” says he, “and took a text without any premeditation, and endeavored to speak what occurred to me at the time. If bad before, it was worse now. I had neither sense nor life, nothing but a poor miserable tone, which produced no effect upon the hearers, and made me really sick of myself. I thought God had nothing to do with me as a preacher. I had no confidence in my own talents and virtues, and the very sound of my voice discouraged me. I have since perceived the great goodness of God herein, preserving me from being puffed up by too good an opinion of my own gifts and graces, which both before and since has proved fatal to many young preachers.”

These views of himself often occasioned him deep distress of mind. He entered the pulpit with dread. He conceived that the mere sight of him there was sufficient to becloud the hearts of his hearers, and intercept every ray of light from heaven. He could not ascertain that he had been the means of the salvation of a single soul during the five years of his preaching. It might have been some relief to him, could he have ventured to develop to some judicious Christian friend the disquietude of his soul. But this he dared not do, lest he should be deemed an unconverted man in the ministry, and exposed as a hypocrite to the world. So he wrapped up the painful secret in his heart, and drank his wormwood alone.

From all this, what are we to infer? That Mr. Evans had never been converted, or was not now in favour with God? We think not. All who knew him had full confidence in his piety, and thought him an excellent Christian. Whether his attention to the subject of baptism, or the Calvinistic views he had recently imbibed, had acted injuriously upon his religious enjoyment, would be an unprofitable speculation, if not otherwise improper. Perhaps these distressing doubts were but the permitted buffetings of Satan, to preserve him from spiritual pride; the preparatory darkness, which enabled him more highly to appreciate, and more earnestly to recommend to others, “the Bright and Morning Star.” Many of God’s chosen servants have been disciplined for their work in darkness. Dr. Payson, during all the earlier part of his eminently useful ministry, and John Summerfield, when his sweet persuasive tongue was leading multitudes to the Cross, were constantly distressed with doubts of their own spiritual condition. Though it is certainly the privilege of every believer to know that he is “a new creature in Christ Jesus,” we cannot thence infer that all such as have not constantly the direct witness of the Spirit are in an unregenerate state.

LABORS IN LEYN.

In 1790, Mr. Evans attended the Baptist association at Maesyberllan, in Brecknockshire. Some ministers from North Wales persuaded him to accompany them on their return. He found the Baptist people at Léyn, in Caernarvonshire, few and feeble. They earnestly besought him to remain with them, to which be at length consented. He was immediately ordained a missionary, to itinerate among several small churches in that vicinity.

Now he began emphatically to “Live by faith of the Son of God.” The burden which he had borne so long, rolled away like that of Bunyan’s Pilgrim. He received “the oil of joy for mourning, and the garment of praise for the spirit of heaviness.” From this time, a wonderous power attended his preaching. Many were gathered into the church, as the fruit of his labor. “I could scarcely believe,” says he, “the testimony of the people, who came before the church as candidates for membership, that they had been converted through my ministry. Yet I was obliged to believe, though it was marvellous to my eyes. This made me thankful to God, and increased my confidence in prayer. A delightful gale descended upon me, as from the hill of the New Jerusalem, and I felt the three great things of the kingdom of heaven, righteousness, and peace, and joy in the Holy Ghost.”

During the first year of his labors in Léyn, he was united in marriage to Miss Catherine Jones, a pious young lady of his own church, and a very suitable companion. After this event, his duties were increasingly arduous. He frequently preached five times during the Sabbath, and walked twenty miles. His heart was full of love, and he spoke with the ardor of a seraph. Constant labor and intense excitement soon wore upon his health. He became feeble, and his friends were apprehensive of consumption. Through the mercy of God, however, he was spared; gradually recovered his strength; and performed, through the remainder of a long life, an incredible amount of ministerial labor.

VISIT TO SOUTH WALES.

Mr. Evans naturally felt a strong desire to see his friends in South Wales. During his second year at Léyn, thinking it might benefit his enfeebled health, as well as refresh his spirit, he determined to make them # visit. He was unable to procure a horse for the journey, and the small societies to which he preached were too poor to provide him one. So he set forth on foot, preaching in every town and village through which he passed. His talents were now developed, and he had received “an unction from the Holy One.”

All who heard him were astonished at his power. His old acquaintances regarded him as a new man. A great awakening followed him wherever he went. Hear his own language:

“I now felt a power in the word, like a hammer breaking the rock, and not like a rush. I had a very powerful time at Kilvowyr, and also pleasant meetings in the neighborhood of Cardigan. The work of conversion was progressing so rapidly and with so much energy in those parts, that the ordinance of baptism was administered every month for a year or more, at Kilvowyr, Cardigan, Blaenywaun, Blaenffds, and Ebenezer, to from ten to twenty persons each month. The chapels and adjoining burying-grounds were crowded with hearers of a week-day, even in the middle of harvest. I frequently preached in the open air in the evenings, and the rejoicing, singing, and praising would continue until broad light the next morning. The hearers appeared melted down in tenderness at the different meetings, so that they wept streams of tears, and cried out, in such a manner that one might suppose the whole congregation, male and female, was thoroughly dissolved by the gospel. ‘The word of God’ was now become as ‘a sharp two-edged sword, dividing asunder the joints and marrow,’ and revealing unto the people the secret corruptions of their hearts. Preaching was now unto me a pleasure, and the success of the ministry in all places was very great. The same people attended fifteen or twenty different meetings, many miles apart, in the counties of Curdigan, Pembroke; Caermarthen, Glamorgan, Monmouth, and Brecknock,

This revival, especially in the vicinity of Cardigan, and in Pembrokeshire, subdued the whole country, and induced people everywhere to think well of religion. The same heavenly gale followed down to Fishguard, Llangloffan, Little New-Castle, and Rhydwylim, where Mr. Gabriel Rees was then a zealous and a powerful preacher. There was such a tender spirit resting on the hearers at this season, from Tabor to Middlemill, that one would imagine, by their weeping and trembling in their places of worship, and all this mingled with so much heavenly cheerfulness, that they “would wish to abide for ever in this state of mind.”

The fame of this “wonderful work of God” spread through South Wales on the wings of the wind. An appointment for Christmas Evans to preach was sufficient to attract thousands to the place. In a very short time he had acquired greater popularity in Wales than any other minister of his day.

SETTLEMENT IN ANGLESEA

On Christmas day, when Mr. Evans was forty-six years of age, he removed from Léyn to the isle of Anglesea. According to his own account, “it was a very rough day of frost and snow.” Unencumbered with this world’s goods, and possessing the true apostolic spirit, he “commenced the journey on horseback, with his wife behind him,” and arrived on the evening of the same day at Llangewin.

Whatever the motive of this removal, it was certainly not the love of money. His salary in Anglesea was only £17 per annum, and for twenty years he never asked for more. He had learned, with the apostle, “having food and raiment, therewith to be content.” He found his reward in his work. The privilege of preaching Christ and saving souls, with him, was preferable to mountains of gold and silver.

On his arrival in Anglesea, he found ten small Baptist societies, and a lukewarm and distracted condition; himself the only minister, and no brother to aid him within a hundred and fifty miles. He commenced his labors in earnest. One of his first movements was the appointment of a day of fasting and prayer in all the preaching places. He soon had the satisfaction to realize an extensive revival, which continued under his faithful ministry for many years,

POWERFUL SERMONS.

In 1794, the South West Baptist Association was held at Velin Voel, in Caermarthenshire. Mr. Evans was invited, as one of the preachers on the occassion. It was a journey of about two hundred miles. He undertook it on foot, with his usual fortitude, preaching at different places as he went along. The meeting was to commence with three consecutive sermons, the last of which was to be preached by Mr. Evans. The service was out of doors, and the heat was very oppressive. The first and second sermons were rather tedious, and the hearers seemed almost stupefied. Mr. Evans arose and began his sermon. Before he had spoken fifteen minutes, scores of people were on their feet, some weeping, some

praising, some leaping and clapping their hands for joy. Nor did the effect end with the discourse. Throughout the evening, and during the whole night, the voice of rejoicing and prayer was heard in every direction; and the dawning of the next day, awaking the few that had fallen asleep through fatigue, only renewed the heavenly rapture.

“Job David, the Socinian,” said the preacher afterwards to a friend, “was highly displeased with this American gale.” But all the Socinians in Wales could not counteract its influence, or frustrate its happy effects.

Mr. Evans continued to visit the associations in South Wales for many years: and whenever he came, the people flocked by thousands to hear “the one-eyed man of Anglesea.’ It was on one of those occasions, and under circumstances somewhat similar to the above, that he preached that singularly effective sermon on the demoniac of Gadara. The meeting had been in progress three days. Several discourses had been delivered with little or no effect.”

Christmas Evans took the stand, and announced as his text the evangelical account of the demoniac of Gadara. He described him as a naked man, with flaming eyes, and wild and fierce gesticulation ; full of relentless anger, and subject to strange paroxysms of rage; the terror and pity of all the townsfolk. They had bound him with great chains, but he would break them as Samson broke the withes. They had tried to soothe him by kindness, but he would leap upon them like a furious wild beast, or burst away with the speed of a stag, his long hair streaming on the wind behind him. He inhabited the rocks of a Jewish cemetery; and when he slept, he laid down in a tomb. The place wasa little out of town, and not far from the great turnpike road, so that people passing often saw him, and heard his dreadful lamentations and blasphemies. Nobody dared to cross his path unarmed, and all the women and children ran away as soon as they saw him coming.

Sometimes he sallied forth from his dismal abode at midnight, like one’ risen from the dead, howling and cursing like a fiend, breaking into houses, frightening the inhabitants from their beds, and driving them to seek shelter in the streets and the fields. He had a broken-hearted wife, and five little children, living about a mile and a half distant. In his intervals of comparative calmness, he would set out to visit them. On his way, the evil spirit would come upon him, and transform the husband and father instantly into a fury. Then he would run toward the house, raving like a wounded tiger, and roaring like a lion upon his prey. He would spring against the door, and shatter it into fragments; while the poor wife and children fled through the back door to the neighbors, or concealed themselves in the cellar. Then he would spoil the furniture, and break all the dishes, and bound away howling again to his home in the cemetery. The report of this mysterious and terrible being had spread through all the surrounding region, and everybody dreaded and pitied the man among the tombs.

Jesus came that way. The preacher described the interview, the miracle, the happy change in the sufferer, the transporting surprise of his long afflicted family. Then, shifting the scene, he showed his hearers the catastrophe of the swine, the flight of the affrighted herdsman, his amusing report to his master, and the effect of the whole upon the populace. All this was done with such dramatic effect, as to convulse his numerous hearers with alternate laughter and weeping for more than half an hour. Having thus elicited an intense interest in the subject, he proceeded to educe from the narrative several important doctrines, which he illustrated so forcibly, and urged so powerfully, that the people first became profoundly serious, then wept like mourners at a funeral, and finally threw themselves on the ground, and broke forth in loud prayers for mercy; and the preacher continued nearly three hours, the effect increasing till he closed.

One who heard that wonderful sermon says, that, during the first half hour, the people seemed like an assembly in a theatre, delighted with an amusing play; after that, like a community in mourning, over some great and good man, cut off by a sudden calamity ; and at last, like the inhabitants of a city shaken by an earthquake, rushing into the streets, falling upon the earth, and screaming and calling upon God!

SANDEMANIANISM AND SABELLIANISM.

About this time arose among the Baptists of North Wales a bitter and distracting controversy, concerning Sandemanism and Sabellianism, which had been introduced by the Rev. Mr. Jones, a man of considerable learning and influence in the denomination.

Mr. Evans was at first inclined to fall in with these doctrines, and participated largely in the strife of tongues. He says:

“The Sandemanian system affected me so far as to quench the spirit of prayer for the conversion of sinners, and it induced in my mind a greater regard for the smaller things of the kingdom of heaven than for the greater. I lost the strength which clothed my mind with zeal, confidence, and earnestness in the pulpit for the conversion of souls to Christ. My heart retrograded, in a manner, and I

could not realize the testimony of a good conscience. Sabbath nights, after having been in the day exposing and vilifying with all bitterness the errors that prevailed, my conscience felt as if displeased, and reproached me that I had lost nearness to, and walking with God. It would intimate that something exceedingly precious was now wanting ih me; I would reply, that I was acting in obedience to the ward; but it continued to accuse me of the want of some precious article.

“I had been robbed, to a great degree, of the spirit of prayer and of the spirit of preaching.”

Mr. Evans thus describes the effect of this controversy upon his people:

“The Sandemanian spirit began to manifest itself in the counties of Merioneth, Caernarvon, Anglesea, and Denbigh, and the first visible effect was the subversion of the hearers, for which the system was peculiarly adapted; intimating, as it did, that to Babylon the crowd of hearers always belonged. We lost, in Anglesea, nearly all those who were accustomed to attend with us; some of them joined other congregations; and, in this way, it pulled down nearly all that had been built up in twelve or fifteen years, and made us appear once again a mean and despicable party in the view of the country. The same effects followed it in a greater or lesser degree in the other counties noticed ; but its principal station appears to have been in Merionethshire ; this county seems to have been particularly prepared for its reception, and here it achieved by some means a sort of supremacy.”

TIME OF REFRESHING

Mr. Evans had been a long time in this controversy, destitute of all religious enjoyment, or, to use his own expressive phrase, “as dry as Gilboa,” when he experienced a remarkable refreshing from the presence of the Lord. The following account is extracted from his journal:

“T was weary of a cold heart towards Christ, and his sacrifice, and the work of his Spirit—of a cold heart in the pulpit, in secret prayer, and in the study. For fifteen years previously, I had felt my heart burning within, as if going to Emmaus with Jesus. On a day ever to be remembered by me, as I was going from Dolgelley to Machynlleth, and climbing up towards Cadair Idris, I considered it to be incumbent upon me to pray, however hard I felt my heart, and however worldly the frame of my spirit was. Having begun in the name of Jesus, I soon felt as it were the fetters loosening, and the old hardness of heart softening, and, as I thought, mountains of frost and snow dissolving and melting within me. This engendered confidence in my soul in the promise of the Holy Ghost. I felt my whole mind relieved from some great bondage: tears flowed copiously, and I was constrained to cry out for the gracious visits of God, by restoring to my soul the joy of his salvation; and that he would visit the churches in Anglesea, that were under my care. I embraced in my supplications all the churches of the saints, and nearly all the ministers m the principality by their names. This struggle lasted for three hours: it rose again and again, like one wave after another, er a high flowing tide, driven by a strong wind, until my nature became faint by weeping and crying. Thus I resigned myself to Christ, body and soul, gifts and labors—all my life—every day and every hour. that remained for me; and all my cares I committed to Christ. The road was mountainous and lonely, and I was wholly alone, and suffered no interruption in my wrestlings with God.

“From this time, I was made to expeet the goodness of God to churches and to myself. Thus the Lord delivered me and the people of Anglesea from being carried away by the flood of Sandemanianism. In the first religious meetings after this, I felt as if I had been removed from the cold and sterile regions of spiritual frost, into the verdant fields of the divine promises. The former striving with God in prayer, and. the longing anxiety for the conversion of sinners, which I had experienced at Léyn, was now restored. I had a hold of the promises of God. The result was, when I returned home, the first thing that arrested my attention was, that the Spirit was working also in the brethren in Anglesea, inducing in them a spirit of prayer, especially in two of the deacons, who were particularly importunate that God would visit us in mercy, and render the word of his grace effectual amongst us for the conversion of sinners.”

COVENANT WITH GOD.

Mr. Evans now entered inte a solemn covenant with Gad, made, as he says, “under a deep sense of the evil of his heart, and in dependence upon the infinite grace and merit of the Redeemer.”

This interesting article is preserved among his papers. We give it entire, as a specimen of his spirit and his faith :

I. “I give my soul and body unto thee, Jesus, the true God, and everlasting life—deliver me from sin, and from eternal death, and bring me into life everlasting. Amen.

II. “I call the day, the sun, the earth, the trees, the stones, the bed, the table, and the books, to witness that I come unto thee, Redeemer of sinners, that I may obtain rest for my soul ftom the thunders of guilt and the dread of eternity. Amen.

III. “I do, through confidence in thy power, eamestly entreat thee to take the work into thine own hand, and give me a circumcised heart, that I may love thee, and create in me a right spirit, that I may seek thy glory. Grant me that principle which thou wilt own in the day of judgment, that I may not then assume pale facedness, and find myself a hypocrite. Grant me this, for the sake of thy most precious blood. Amen.

IV. “I entreat thee, Jesus, the Son of God, in power, grant me, for the sake of thy agonizing death, a covenant-interest in thy blood, which cleanseth; in thy righteousness, which justifieth; and in thy redemption, which delivereth. I entreat an interest in thy blood, for thy blood’s sake, and a part in thee, for thy name’s sake, which thou hast given among men. Amen.

V. “O Jesus Christ, Son of the living God, take, for the sake of thy cruel death, my time, and strength, and the gifts and talents I possess; which, with a full purpose of heart, I consecrate to thy glory in the building up of thy church in the world, for thou art worthy of the hearts and talents of all men, Amen.

VI. “I desire thee, my great High Priest, to confirm, by thy power, from thy High Court, my usefulness as a preacher, and my piety as a Christian, as two gardens nigh to each other; that sin may not have place in my heart, to becloud my confidence in thy righteousness, and that I may not be left to any foolish act that may occasion my gifts to wither, and rendered useless before my life ends. Keep thy gracious eye upon me, and watch over me, O my Lord, and my God for ever! Amen.

VII. “I give myself in a particular manner to thee, O Jesus Christ, the Saviour, to be preserved from the falls into which many stumble, that thy name (in thy cause) may not be blasphemed or wounded, that my peace may not be injured, that thy people may not be grieved, and that thine enemies may not be hardened. Amen.

VIII. “I come unto thee, beseeching thee to be in covenant with me in my ministry, As thou didst prosper Bunyan, Vavasor Powell, Howell Harris, Rowlands, and Whitefield, O do thou prosper me. Whatsoever things are opposed to my prosperity, remove them out of the way. “Work in me every thing approved of God, for the attainment of this. Give me a heart ‘sick of love’ to thyself, and to the souls of men. Grant that I may experience the power of thy word before I deliver it, as Moses felt the power of his own rod, before he saw it on the land and waters of Egypt. Grant this, for the sake of thine infinitely precious blood, O Jesus, my hope, and my all in all! Amen.

IX. “Search me now, and lead me in plain paths of judgment. Let me discover in this life what I am before thee, that I may not find myself of another character, when I am shown in the light of the immortal world, and open my eyes in all the brightness of eternity. Wash me in thy redeeming blood: Amen.

X. “Grant me strength to depend upon thee for food and raiment, and to make known my requests. O let thy care be over me as a covenant-privilege betwixt thee and myself, and not like a general care to feed the ravens that perish, and clothe the lily that is cast into the oven; but let thy care be over me as one of thy family as one of thine unworthy brethren. Amen.

XI. “Grant, O Jesus! and take wpon thyself the preparing of me for death, for thou art God; there is no need, but for thee to speak the word. If possible, thy will be done; leave me not long in affliction, nor to die suddenly, without bidding adieu to my brethren, and let me die in their sight, after a short illness. Let all things be ordered against the day of removing from one world to another, that there be no confusion nor disorder, but a quiet discharge in peace. O grant me this, for the sake of thine agony in the garden! Amen.

XII. “Grant, O blessed Lord! that nothing may grow and be matured in me, to occasion thee to cast me off from the: service of the sanctuary, like the sons of Eli; and for the sake of thine unbounded merit, let not my days be longer than my usefulness. O let me not be like lumber in a house in the end of my days,—in the way of others to work. Amen.

XIII. “I beseech thee, O Redeemer! to present these my supplications before the Father: and O! inscribe them in thy book with thine own immortal pen, while I am writing them with my mortal hand, in my book on earth. According to the depths of thy merit, thine undiminished grace, and thy compassion, and thy manner unto thy people, O! attach thy name, in thine upper court, to these unworthy petitions ; and set thine amen to them, as I do on my part of the covenant. Amen.

—Christmas Evans, Llangevni, Anglesea, April 10, 18—.”

Mr. Evans, in speaking of this solemn transaction and its influence upon his spirit, subsequently observes: ‘I felt a sweet peace and tranquillity of soul, like unto a poor man that had been brought under the protection of the royal family, and had an annual settlement for life made upon him; from whose dwelling the painful dread of poverty and want had been for ever banished away.”

Thus “strengthened with might in the inner man,” he labored with renewed energy and zeal, and showers of blessings descended upon his labors. In two years, his ten preaching places in Anglesea were increased to twenty, and six hundred converts were added to the church under his care. “The wilderness and solitary place were glad for them, and the desert rejoiced and blossomed as the rose.”

STUDYING THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE,

Mr. Evans made several visits to Liverpool, Bristol, and other parts of England. On these occasions he was frequently solicited to preach in English, to which he several times consented, to the great gratification of his English friends.

“These sermons evinced the same energy of thought, and the same boldness of imagery, as those which he preached in Welsh; but in the power of his peculiar delivery, they were inevitably far inferior. His brethren in England were much delighted with his performances, and said it was “no wonder the Welsh were warm under such preaching;” but his language was broken and hesitating, and they could scarcely have any conception of his animation and energy when he spoke in his vernacular tongue.”

His success induced him to commence a systematic study of the English language, that he might be able to preach in it with greater freedom and effect. He could read English before, and was somewhat familiar with the best English authors of his day; but never acquainted himseélf with the grammar of the language till he was thirty-three years of age. But read his own account of the matter:

“The English brethren had prevailed upon me to preach to them in broken English, as it was; this induced me to set about the matter in earnest, making it a subject of prayer, for the aid of the Spirit, that I might be in some measure a blessing to the English friends, for there appeared some sign that God now called me to this department of labor in his service. I never succeeded in anything for the good of others, without making it a matter of prayer. My English preaching was very broken and imperfect in point of language; yet, through the grace of Jesus Christ, it was made in some degree useful at Liverpool, Bristol, and some other places. I was about forty years old when I learned to read the Hebrew Bible and the Greek Testament, and use Parkhurst’s Lexicons in both languages. I found that, had I studied the English language attentively and perseveringly, I should be able to overcome great difficulties; and also, that I could without much labor im the course of few years, even in my idle hours, as it were, understand all the Hebrew words corresponding with every Welsh word in the Bible; and so also the Greek. I had always before thought that it was impossible to accomplish this, fot I had no one to encourage me in the undertaking; but I found it was practicable, and proved it in some measure, yet relinquished the pursuit on account of my advanced age.”

Evans most famous sermon, The World as a Graveyard, is found in several English versions (as Evans usually preached in Welsh).

“Methinks I find myself standing upon the summit of one of the highest of the everlasting hills, permitted thence to take a survey of our earth. It shows to me a wide and far-spread burial-ground, over which lie scattered in countless multitudes the wretched and perishing children of Adam. The ground is full of hollow’s, the yawning caverns of death, while over it broods a thick cloud of fearful darkness. No light from above shines upon it, nor is the ray of the sun or moon, or the beams of a candle seen through all its borders. It is walled around. Its gates, large and massive, ten thousand times stronger than all the gates of brass forged among men, are one and all safely locked.

It is the hand of Divine Justice that has locked them, and so firmly secured are the strong bolts which hold those doors, that all the created powers even of the heavenly world, were they to labor to all eternity, could not drive so much as one of them back. How hopeless the wretchedness to which the race are doomed, and into what irrecoverable depths of ruin has the disobedience of their first parent plunged them!

“But behold, in the cool of the day there is seen descending from the eternal hills in the distance, the radiant form of Mercy, seated in the chariot of the divine promise, and clothed with splendor, infinitely brighter than the golden rays of the morning when seen shooting over mountains of pearls. Seated beside Mercy in that chariot is seen another form like unto the Son of man. His mysterious name is the ‘Seed of the Woman,’ and girt around him shines the girdle of eternity, radiant with the lustre of the heaven of heavens. ‘He has descended into the lower parts of the earth.’ I see Mercy alight from that chariot, and she is knocking at the huge gate of this vast cemetery.

She asks of Justice: ‘Is there no entrance into this field of death? May I not visit these caverns of the grave, and seek, if it may be, to raise some names at least of the children of destruction, and bring them again to the light of day? Open, Justice, open; drive back these iron bolts and let me in, that I may proclaim the jubilee of deliverance to the children of the dust.’

But I hear the stern reply of Justice from within those walls; it is,—‘Mercy, surely thou lovest Justice too well, to wish to burst these gates by force of arm, and thus obtain entrance by mere lawless violence. And I cannot open the door. I cherish no anger towards the unhappy wretches. I have no delight in their eternal death, or in hearing their cries as they lie upon the burning hearth of the great fire kindled by the wrath of God, in the land that is lower than the grave. But I am bound to vindicate the purity, holiness, and equity of God’s laws; for, ‘without shedding of blood there is no remission.’

‘Be it so,’ said Mercy, ‘but wilt thou not accept of a surety who may make a sufficient atonement for the crime committed and the offence given?’ ‘That will I,’ said Justice, ‘only let him be duly allied to either party in this sad controversy, a kinsman, near alike to the injured Lawgiver, and to the guilty tenants of the burial-ground.’ ‘Wilt thou, then,’ said Mercy, ‘accept of the puissant Michael, prince among the hosts of heaven, who fought bravely in the day when there was war in heaven, and also vanquished Apollyon upon the summit of the everlasting hills?’ ‘No,’—said Justice, ‘I may not, for his goings forth are not from the beginning, even from everlasting.’

‘Wilt thou not then accept of the valiant Gabriel, who compelled Beelzebub to turn and seek safety in flight from the walls of the heavenly city?’ ‘No,’—cried Justice, ‘for Gabriel is already bound to render his appointed service to the King Almighty; and who may serve in his place while he should be attempting the salvation of Adam’s race? There needs,’ continued Justice, ‘one who has, of right belonging to him, both omnipotence and eternity, to achieve the enterprise. Let him clothe himself with the nature of these wretches. Let him be born within these gloomy walls, and himself undergo death within this unapproachable place, if he would buy the favor of Heaven for these children of the captivity!’

“But while this dialogue was held, behold, a form fairer than the morning dawn, and full of the glory of heaven, is seen descending from that chariot. Casting, as he passes, a glance of infinite benignity upon the hapless tenants of that burial-ground, he approaches, and asks of Justice: ‘Wilt thou accept of me?’ ‘I will,’ said Justice, ‘for greater art thou than heaven and the whole universe.’

“‘Behold, then,’ said the stranger, ‘I come: in the volume of the book has it been written of me. I will go down, in the fulness of time, into the sides of the pit of corruption. I will lay hold of this nature, and take upon me the dust of Eden, and, allied to that dust, I will pour into thy balance, Justice, blood of such worth and virtue that the court of heaven shall pronounce its claims satisfied, and bid the children of the great captivity go free.’

“Centuries have rolled by, and the fulness of time is now accomplished; and see, an infant of days is born within the old burial ground of Eden. Behold a Son given to the dwellers of the tomb, and a spotless Lamb, the Lamb of God, is seen within that gloomy enclosure. When the hour came at which the ministers of the Divine Justice must seize upon the victim, I see them hurrying towards Gethsemane. There, in heaviness and sorrow of soul, praying more earnestly, the surety is seen bowed to the earth, and the heavy burden he had assumed is now weighing him down. Like a lamb, he is led towards Golgotha—the hill of skulls.

There are mustered all the hosts of darkness, rejoicing in the hope of their speedy conquest over him. The monsters of the pit, huge, fierce, and relentless, are there. The lions, as in a great army, were grinding fearfully their teeth, ready to tear him in pieces. The unicorns, a countless host, were rushing onwards to thrust him through, and trample him beneath their feet. And there were the bulls of Bashan, roaring terribly; the dragons of the pit are unfolding themselves, and shooting out their stings, and dogs many are all around the mountain.

‘It is the hour and power of darkness.’ I see him passing along through this dense array of foes, an unresisting victim. He is nailed to the cross; and now Beelzebub and all the master-spirits in the hosts of hell have formed, though invisible to man, a ring around the cross. It was about the third hour of the day, or the hour of nine in the morning, that he was bound as a sacrifice, even to the horns of the altar. The fire of divine vengeance has fallen, and the flames of the curse have now caught upon him. The blood of the victim is fast dropping, and the hosts of hell are shouting impatiently: ‘The victory will soon be ours.’ And the fire went on burning until the ninth hour of the day, or the hour of three in the afternoon, when it touched his Deity,—and then it expired.

For the ransom was now paid and the victory won. It was his. His hellish foes, crushed in his fall, the unicorns and the bulls of Bashan retreated from the encounter with shattered horns; the jaws of the lions had been broken and their claws torn off, and the old dragon, with bruised head, dragged himself slowly away from the scene, in deathlike feebleness. ‘He triumphed over them openly,’ and now is He for ever the Prince and Captain of our salvation, made perfect through sufferings. The graves of the old burial-ground have been thrown open; and from yonder hills gales of life have blown down upon this valley of dry bones, and an exceedingly great army have already been sealed to our God, as among the living in Zion.”

Featured Image Credit: Sermons of Christmas Evans, by Joseph Cross. www.gutenberg.org/files/42340/42340-h/42340-h.htm.

Related

Sorry, no records were found. Please adjust your search criteria and try again.

Sorry, unable to load the Maps API.