Much of John Jasper’s childhood and teenaged years were spent working at both Peachy Plantations, one located in Fluvanna County and the other near the city of Williamsburg. At the age of twenty-five, he was sold to Samuel Hargrove, “a devout member and deacon of the First Baptist Church of Richmond.” (www.preaching.com) His relationship with Hargrove would forever change the trajectory of his life. Two years after his acquisition, on his birthday no less, the twenty-seven-year old John was born again while working at his master’s tobacco factory. In John’s own words:

“My sins was piled on me like mount’ns; my feet was sinkin’ down to de reguns of despar, an’ I felt dat of all sinners I was de wust. I tho’t dat I would die right den, an’ wid what I supposed was my lars breath I flung up to heav’n a cry for mercy. ‘Fore I kno’d it, de light broke; I was light as a feather; my feet was on de mount’n; salvation rol’d like a flood thru my soul, an’ I felt as if I could ‘nock off de fact’ry roof wid my shouts.” (Hatcher, pg. 25)

John immediately began spreading the word about his newfound faith; in fact, he claimed that his call to the Gospel ministry occurred on the same day as his salvation. Jasper didn’t let his lack of a formal education deter him from his calling. With a burning passion and Mr. Hargrove’s permission, he traveled all over the state preaching the Gospel, most often at the funeral services of fellow slaves but periodically at Third Baptist Church in Richmond. It was said that no slave family wanted to send their loved one on to glory without a sermon from John Jasper (Thomas Ray, “John Jasper – Unmatched Orator”). His popularity was an enigma of sorts; to hear William Hatcher describe Jasper’s unique style of preaching, you would think that no one would be interested. Such was not the case, though:

“Shades of our Anglo-Saxon Fathers! Did mortal lips ever gush with such torrents of horrible English! Hardly a word came out clothed and in its right mind. And gestures! He circled around the pulpit with his ankle in his hand; and laughed and sang and shouted and acted about a dozen characters within the space of three minutes. Meanwhile, in spite of these things, he was pouring out a gospel sermon red hot, full of love, full of invective, full of tenderness, full of bitterness, full of tears, full of every passion that ever flamed in the human breast. He was a theater within himself …”

Hatcher also tells the story of a white minister’s shock that a negro would be his associate at a funeral service. His solution to the problem was to have Jasper wait outside the church while he conducted the service inside; of course, the audience that day (many of whom attended the funeral because Jasper was to preach) would have nothing to do with the minister’s foolhardy plan:

“Tumultuously they cried out for Jasper, a cry in which the whites outdid the blacks. It was not in Jasper to ignore such appreciation. Of all men, he had the least desire or idea of being snubbed or sidetracked. With that mischievous smile which was born of the jubilant courage of his soul, Jasper came forth. He knew well the boundaries of his rights, and needed no danger signals to warn him off hostile ground. For fifteen or twenty minutes he poured forth a torrent of passionate oratory, not empty and frivolous words, but a message rich with comfort and help, and uttered only as he could utter it. The effect was electrical. The white people crowded around him to congratulate and thank him, and went away telling the story of his greatness.” (Hatcher, pg. 43)

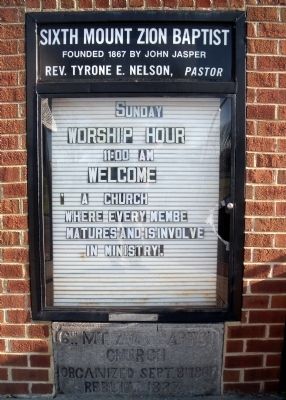

In April of 1865, Jasper was granted his freedom, and two years later (at the age of fifty-five), he started the Sixth Mt. Zion Baptist Church with nine charter members (called “Sixth” because it was the sixth black Baptist church in Richmond). Although he changed the nature of his ministry, the ministry never changed his consuming desire for people to come to know Christ as their personal Savior. By the time he died in 1901, history records that his church was ministering to well over 2,000 members and many more in the community at that time.

Jasper’s most famous sermon, “De Sun Do Move”, was both predictable and persuasive. Predictable because he had no formal training (the sermon defended a geocentric theory of the universe based on Joshua 10:13), but persuasive because he argued his position from Scripture, and it vilified the Darwinism of his day. In fact, a reporter from Richmond said:

“I was surprised, but managed to get into Mt. Zion. I laughed when I should and I cried too. Jasper’s respect for the Bible and his keen wit, his power in pathos was irresistible…In closing his sermon Jasper said, ‘Whenever ye see a fourloserfer wat contradicts God’s Word, tell him, Good Night!’ The old rascal turned to the White ladies and said, ‘I see de bloom uv kulchur in youh faces. Think it over! I wants ever’ one te vote. If you believes de sun do move, hole up youh han!’ My hand went up. But I did not vote that the sun moved. I voted for John Jasper.” (Wayne E. Croft Sr., “John Jasper: Preaching with Authority”)

It is said that Jasper preached this sermon over 250 times, including one time to the Virginia General Assembly. In it he also asserted that the earth was flat because Revelation 7:1 says that the angels stood at the “four corners of the earth.” His complete devotion to the veracity and authority of the Bible is a model for today’s preacher. Granted … in contrast to Jasper, every preacher today must employ a biblical hermeneutic and avoid proof-texting any conclusion, but every preacher ought to say confidently (as Jasper did on many occasions), “These are not Jasper’s words but the Bible’s, and I believe in the Word of God.”

From http://places.afrovirginia.org/items/show/389

Large numbers of African Americans were drawn to Jasper’s charismatic ministry. The rapidly growing congregation moved to its present location in 1869, and is credited with being the first church in the city of Richmond that was organized by an African- American preacher. Promoted by the local newspapers, black and white Richmonders flocked to the church to hear Jasper’s celebrated sermons. He reached the pinnacle of his career when he delivered his sermon “De Sun Do Move,” from the pulpit of Sixth Mount Zion Church. It was a powerful statement of faith that became famous all over the United States and abroad.

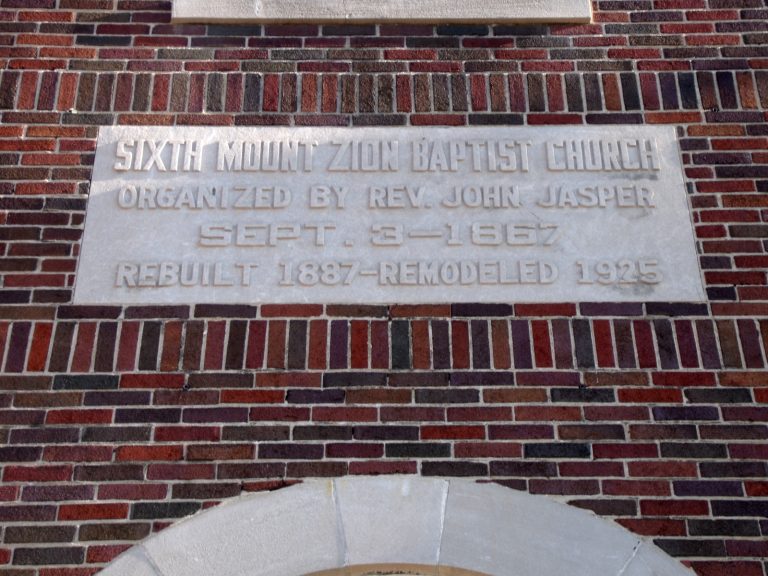

The Sixth Mount Zion church building remains one of the few 19th-century structures that can conclusively be attributed to an African-American builder, and continues to serve as a significant expression of African American ecclesiastical architecture. George W. Boyd designed and built the current church structure in 1887 and the noted African American architect, Charles T. Russell, remodeled it in 1925. Boyd is particularly significant because he was one of only a handful of African-American builders who were licensed to build in 19th-century Richmond. Charles T. Russell is also an important figure as the first professional African-American architect in Richmond in the 20th century. Both men are also credited with the construction and renovation of the Maggie L. Walker House, also located within Richmond’s Jackson Ward District.

Sixth Mt Zion is the “Mother Church” of two thriving Richmond congregations–Trinity Baptist Church (1906) and Greater Mount Moriah Baptist Church (1924).

The Commonwealth of Virginia has recognized the church with two historical highway markers–one at the church site in downtown Richmond, and another in Fluvanna County near the birthplace of John Jasper. Residing within the historic Jackson Ward District, the church is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and the Virginia Landmarks Register. In 2004, the Richmond City Council honored the church with a special designation as a local “historic district,” encompassing the 3 acres of land on which it stands, the only black church in Richmond to receive this distinction.

Regarded as one of the nation’s pioneering churches in the field of historic preservation, the church opened its John Jasper Memorial Room and Museum in January 1926. Bibles, books, paintings, clothing, ceremonial artifacts, and furniture make up the memorabilia that visitors see when they visit. Chief among these items are a golden bust of John Jasper made in 1904, a rare stone taken from Mount Zion in Jerusalem, presented to the church in 1924, and a commemorative quilt. The 10×15 foot historical quilt was created in 1997 to mark the church’s 130th anniversary and is composed of 40 panels portraying the many organizations which make up church life.

Seven pastors have led Sixth Mount Zion during its long history, including Dr. Augustus Walter (A.W.) Brown who served for over forty-three years until his death in 1967. Greatly admired for his leadership and faithful dedication to missionary work throughout Europe and the Caribbean, Dr. Brown was instrumental in defending the church from destruction when Interstate 95 was built in downtown Richmond, Virginia in 1957.

Over 700 homes of African Americans were demolished and hundreds of residents forced to move, resulting in the destruction of the central portion of the Jackson Ward community. The church congregation stood firm in its determination not to be destroyed, and was given three alternatives by the highway authorities: have the church demolished and reconstructed elsewhere, move the church away from the path of the highway, or have the highway swing north around the back of the church. The third alternative prevailed, due in part to the church’s association with John Jasper, and today the church stands high above the Interstate, a prominent landmark along the east coast’s major north-south thoroughfare.

Physical Description

Sixth Mount Zion’s proximity to downtown Richmond has placed it among the prominent features of the city’s skyline, and it is a superb example of Gothic Revival “high-style” architecture using wire-cut brick and limestone. A series of original stained glass windows adorn the main sanctuary. Each window is composed of tan and cream colored “Art Glass” with a scallop motif at the crown of each window. One special window, dedicated in John Jasper’s memory, depicts a garden scene lined with lilies and roses with a sundial as its centerpiece, commemorating Jasper’s famous sermon. These impressive windows now light a sanctuary seating more than a thousand people, making Sixth Mount Zion one of Richmond’s largest African-American churches.

Featured Image Credit: https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=5600

Related

Sorry, no records were found. Please adjust your search criteria and try again.

Sorry, unable to load the Maps API.